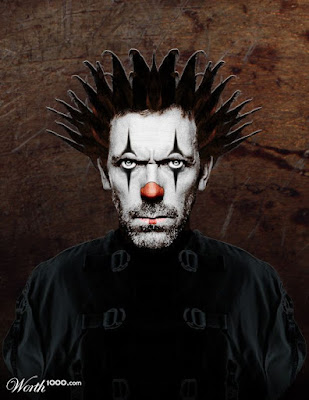

Creepy Killer Clowns

Wednesday 8 November 2017

Monday 18 September 2017

AMERICAN HORROR STORY: CULT and Scary Clowns Throughout History

Ryan Murphy and Brad Falchuk really love scary clowns. Throughout American Horror Story‘s seven seasons, the pair has played on people’s discomfort around the oil painted faces of childhood entertainers. This season, they’ve turned the clown terror up to 11. AHS: Cult has seen the return of the horrifying child killer/immortal wandering ghost murderer, Twisty the Clown. At the same time, a roving band of killer clowns has been bringing Sarah Paulson‘s Ally to her knees through her immobilizing coulrophobia. If we weren’t all already in agreement, clowns are officially terrifying again.

But why have clowns become such a creepy cultural touchstone? When did the Evil Clown trope first become popular? We’ve delved into the long and twisted history of these murderous circus folk for your eerie enjoyment.

From pop culture to true crime, Evil Clowns have saturated modern horror for at least two decades. But way back in the early 1800s there was a more famous face of clowning: Joseph Grimaldi. A renowned character in the London theatre circuit, Grimaldi first used the white makeup that has become synonymous with clowns everywhere. Though never playing a murderous clown himself, the paintings of Grimaldi–like pretty much every painting from the Victorian times–are unfeasibly terrifying, making it easy to see why they’ve become so feared.

Grimaldi wasn’t the only famous clown of the era. In the 1800s, a small trend of operas about murderous clowns took center stage in what can probably be called the first appearance of the Evil Clown trope. La Femme de Tabarin and Pagliacci portray Lifetime movie-esque love triangles in which the betrayed husband also just happens to be a clown… like we said, it was a weird and terrifying time. Strangely, these weren’t the only killer clown relationship dramas of the time, just the most well known. Both were constantly dogged by rumors of plagiarism from creators of the lesser known murder clown operas. Theatrical beefs aside, one thing was for sure: the idea of clowns as murderous monsters had been unleashed on the public.

When Bill Finger and Bob Kane created Batman, they took from what they saw as a primal fear of bats and crafted a dark and noir-ish hero who needed an equally terrifying villain. Though he’s become synonymous with the Caped Crusader now, The Joker–created along with artist Jerry Robinson–was originally meant to die after his second appearance. Ultimately, his impact was too large and the Clown Prince of Crime lived to see another day. The creators added inspiration from Conrad Veidt’s performance in a silent film called The Man Who Laughs, and another generation of coulrophobes were born.

Though the horror of fictional clowns was already in the cultural conscience, serial killer John Wayne Gacy cemented clowns as eternal horror fodder when it was revealed that the mass murderer also worked children’s birthday parties as character named Pogo the Clown. Shortly after Gacy’s arrest and subsequent trial, the murderous clown made a cinematic comeback with movies like Killer Klowns From Outer Space and Clownhouse. And let’s not forget that Michael Myers himself is dressed as a clown when he commits his first murder on that fateful Halloween night. Soon a television miniseries would changed the cultural landscape of creepy clowns and certified the trope as solid gold. That series was called It.

Pennywise the Clown is arguably the most infamous creepy clown of all time. Stephen King‘s killer creation was brought to life by Tim Curry in the 1990 classic and went on to scare children and adults alike for decades. Pennywise was the white-faced red-nosed nightmare that truly put evil clowns on the map. From then on, there was no stopping our collective imaginations where clowns were concerned. That led to numerous fantastically trashy movies like The Clown at Midnight, which incidentally has kids being stalked by an evil Pagliacci opera clown.

Rob Zombie‘s horror homage House of 1000 Corpses introduced the ’00s to Sid Haig’s Captain Spalding, a grease paint clown who loved fried chicken and a whole lot of murder, igniting a brand new wave of frightening clown movies. But it was Heath Ledger‘s portrayal of the Joker in 2008’s The Dark Knight that would influence Halloween costumes and Hot Topic for nearly a decade. His chaotic clown was a more realistic rendering of the trope and had a massive cultural impact.

As is the way, art imitates life and life imitates art. Last year we began to see a spate of spooky clown sightings and hear ominous rumors of murderous clowns trying to lure children into dark woods. These stories quickly gained prominence, with viral videos and photos proliferating online, creating a truly modern urban legend and setting the perfect scene for this year’s It remake.

So, here we are in 2017. With It smashing box office records and American Horror Story: Cult exploiting coulrophobia for all it’s worth, it’s clear creepy clowns are here to stay. Who are your favorite killer clowns? Did we miss anything in our horrific history?

A Brief History of Creepy Clowns

The spectre of the “creepy clown” has gotten a lot of attention as of late. Beginning in August 2016, creepy (and fake) clown sightings spread across the U.S. and other countries, creating a kind of viral clown panic. And as summer came to a close in 2017, killer clowns came for American audiences in the TV show American Horror Story: Cult and the film remake IT, which earned $123 million at the box office on its opening weekend.

Why exactly have creepy clowns become such a trope in pop culture? After all, didn’t they used to be happy and cheerful? Well, not exactly, according to Benjamin Radford, author of Bad Clowns.

“It’s a mistake to ask when clowns went bad,” he says, “because they were never really good.”

The “trickster,” he explains, is one of the oldest and most pervasive archetypes in the world (think Satan in the Bible). The trickster can be both funny and scary, and he (it’s usually a “he”) makes it hard for others to tell whether he’s lying. Clowns are a type of trickster that have been around for a long time—one of the most recognizable is the harlequin, a figure who emerged in Italian commedia dell’arte theatre in the 16th century.

The harlequin was known for his colorful masks and clothing with diamond-shaped patterns, and often served as the comical, amoral servant in plays that toured throughout Europe. These plays also inspired a clownish puppet named “Punch,” who appeared in British shows starting in at least the 18th century. The character would later be written into a popular puppet show called “Punch and Judy,” in which Punch cracked jokes, beat his wife, and murdered his child.

Punch is a “gleeful madcap colorful character, but he’s also this horrific monster,” Radford says, noting that creepy clowns appeal across age groups, not only to kids, but to teens and adults as well. “It’s this strange mix of horror and humor that has always drawn us to clowns.”

Bad—or at least, sad—clowns continued to appear in European culture throughout the 19th century. Charles Dickens’ novel The Pickwick Papers (1836) featured an alcoholic clown; and in the 1880s and ‘90s, both a French play and an Italian opera centered on murderous clowns (one play was accused of plagiarizing the other).

These complicated clowns made it to America, too. In 1924, U.S. audiences met a bitter and vengeful clown in the silent film He Who Gets Slapped. A decade and a half later, a prankster villain named the Joker make his debut in a Batman comic. And even though Emmett Kelly, Jr., one of the most famous American circus clowns in the early 20th century, was no villain, neither was he cheerful. Rather, his “Weary Willie” character was a hobo clown with a painted-on frown.

But then came a change. In the 1950s and ‘60s, American television introduced audiences to a couple of new clowns who were always happy.

“Ronald McDonald being in commercials spread ‘the happy clown’ across the country,” Radford says of the fast food mascot. “Same thing with Bozo the Clown. There were dozens of Bozos in different regions that were very, very popular during the era. So it was really television that helped propel the sort of default happy/good clown into the public’s consciousness.”

Yet by the late 1970s and early ‘80s, the American image of the clown was already shifting again, this time toward something more sinister. One of the influences in this shift was the media coverage of John Wayne Gacy, a serial murderer who had occasionally dressed as “Pogo the Clown.” Radford notes that Gacy was not a professional clown, and that he didn’t dress up as Pogo very often or use his costume to lure children (his victims were teenagers and young men). But once in jail, Gacy helped cultivate his image as a killer clown in the media by drawing self-portraits of himself as Pogo.

Then came IT, the Stephen King novel about a scary, supernatural clown who lurks around the suburbs and murders children (this was part of a bigger shift toward scary suburban scenarios in the horror film genre). After the novel came out in 1986, it was adapted into a TV movie starring Tim Curry as Pennywise the Dancing Clown.

Which means that once again, television brought a new clown into people’s living rooms—a threatening, child-harming one—that recent creepy clown panics suggest viewers have not shaken since. In 2013, residents in the U.K. town of Northampton were alarmed by a man who wandered around town wearing a mask reminiscent of Curry’s Pennywise and occasionally yelled out lines from the movie (turns out it was just some 22-year-old causing problems).

The United States’ 2016 clown panic, too, had echoes of IT’s mystical, murderous villain. King certainly didn’t invent the evil clown. But he may have helped make Americans paranoid that one could be lurking outside their doors.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)